The Invisible Contract

Society’s Gender Trap and the Dysphoria It’s Manufacturing in Our Kids

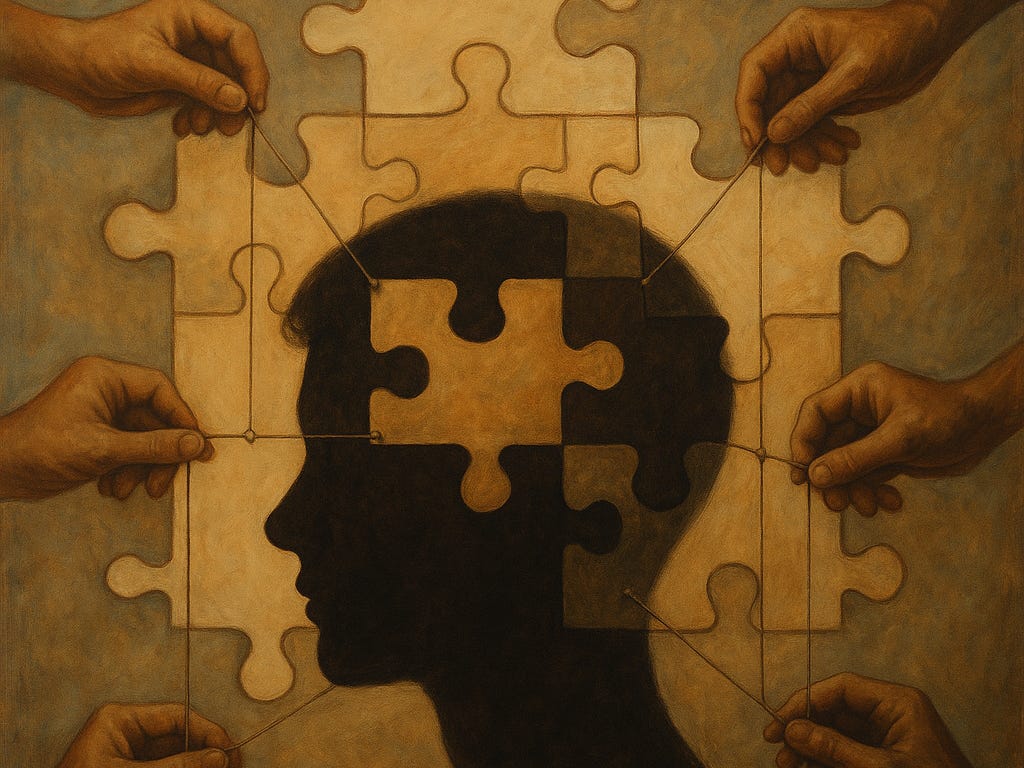

The Hidden Architecture of Expectation

Picture this: a seven-year-old boy reaches for a doll during playtime—not because he’s “trans,” but because it’s there, and curiosity doesn’t care about pink or blue. Mom smiles, “That’s so sweet—what a caring little soul.” A decade later, the same boy is anxious, hollowed out by an unnamed pressure. The world calls it gender dysphoria—an innate mismatch between mind and body, a signal to intervene medically. But what if this isn’t the voice of biology at all? What if it’s the echo of a contract he never signed—an invisible pact made through praise, approval, and subtle obligations that tether belonging to performance?

This is the premise of psychological contract theory (PCT)—a research tradition that began in the 1960s within industrial/organizational psychology and grew into a broader lens on human relationships. Originally developed to explain why workers felt betrayed by employers, it offers an uncanny blueprint for the psychological and physiological dynamics now misread as “gender identity” and “dysphoria.”

At its heart, PCT explains how unspoken expectations and perceived obligations govern behaviour—and how their breach gives rise to emotional distress. That same machinery underpins the way children internalize gender norms, not as optional roles, but as requirements for love, safety, and belonging. When they fail to meet those requirements—or when those requirements contradict their authentic impulses—the resulting tension manifests as dissonance, alienation, or, in modern language, dysphoria.

It’s been almost 20 years since I last contributed to PCT—extending it to non-traditional relationships to map how mostly unspoken expectations/obligations shape behaviour and distress. The same blueprint illuminates what’s happening to children under today’s gender paradigm. It isn’t a mystical inner essence; it’s a social contract—roles, jobs, and behaviours we paste onto kids as the price of belonging. When they can’t keep paying, the distress we label “dysphoria” often looks like the predictable fallout from a breached contract.

This piece bridges disciplines—sociology, developmental psychology, and my PCT lens—to show why the problem isn’t the child. It’s the environment that scripts them.

To understand this dynamic, we must first clarify what “gender” actually means. Despite decades of ideological fog, the sociological and institutional consensus is clear: gender refers to the social roles, behaviours, occupations, and expectations that societies associate with being male or female. It is not biological sex, but rather the cultural performance built around it—who nurtures, who provides, who leads, who serves. Historically, gender described the visible scaffolding of civilization: the division of labour, clothing, professions, emotional expression, even moral expectations. When we say a girl is “feminine” or a boy is “masculine,” we are referencing this catalogue of assigned functions. Gender, therefore, is not a feeling but a social contract—a negotiated agreement between the individual and the environment about what behaviour earns belonging and what deviation risks exclusion.

The Birth (and Reach) of the Psychological Contract

The idea was first articulated by Chris Argyris in 1960 and expanded by Denise Rousseau in the late 1980s. Argyris, studying factory workers in Ohio, noticed something perplexing: employees often felt betrayed by management, even when no formal promises had been made. The grievance wasn’t about pay or policy—it was about expectations.

They believed that loyalty, effort, and obedience would be reciprocated with care, stability, and respect, more often than not, implicitly believing this and without the necessary mechanisms to explain such, apart from a singular term, “fairness.” When that unspoken reciprocity broke, productivity collapsed, and workers generally lost interest in pursuing greatness and achievement. Rousseau later coined the term “psychological contract” to describe this invisible ledger of give-and-take—the web of perceived commitments that bind individuals to institutions, and institutions to individuals.

PCT divided these exchanges into two broad forms:

Transactional contracts—explicit, short-term exchanges (e.g., “Do X for reward Y”).

Relational contracts—implicit, emotional, long-term obligations (e.g., “Be loyal, and we’ll protect you.”)

Breach one, and you get dissatisfaction. Breach the other, and you get an identity crisis.

The elegance of the theory is its universality: it applies wherever expectations and obligations are perceived—between lovers, teachers and students, citizens and governments, even in the product you bought that didn’t meet your expectations. Over time, scholars began to extend PCT beyond the workplace to education, healthcare, and family systems, observing that the same unspoken exchanges structured these relationships.

In classrooms, for example, students form psychological contracts with teachers and institutions—expecting fairness, mentorship, and opportunity in exchange for effort and obedience. When those expectations are unmet, motivation and self-concept erode. In families, similar exchanges govern emotional climates: a child learns that certain behaviours—quietness, helpfulness, toughness—secure affection, while others threaten withdrawal.

Every smile, correction, or withheld glance writes another clause—often unintentionally, and often unnoticed by the very person who ends up carrying the contract.

From Factories to Families: The Child as Contracted Subject

By the 1980s, developmental psychology had begun mapping how social expectations shape identity formation. Piaget and Vygotsky emphasized that children build schemas—internal models of the world—through feedback loops with caregivers and peers. Attachment theorists later showed how parental responsiveness creates mental templates for safety and self-worth.

But what these theories described implicitly, PCT made explicit: these are contracts, complete with terms, obligations, and breach consequences.

A child learns that certain performances guarantee belonging. “Good boy.” “What a pretty girl.” “That’s not ladylike.” “Be strong.” “You’re so sweet.” “That’s cute.” Each phrase is a micro-transaction: behaviour traded for approval and connection. Over time, these exchanges crystallize into an internalized belief—this is who I must be to be loved. The irony: it’s the opposite of true belonging. Layer neurodivergence on top—an autistic child who masks to reduce social friction, a highly sensitive child who over-reads cues—and the performance intensifies. The “contract” becomes an operating system.

The problem is that these early “agreements” are not negotiated; they’re imposed. And they are reinforced not through coercion, but through care.

When a child explores—crosses gendered lines of play, curiosity, or emotion—the adult world often responds with praise that seems benevolent but encodes expectation. A boy who nurtures a doll or shows kindness and empathy towards a sibling is called “sweet” or “cute.” A girl who climbs trees is “brave” or “courageous.” Each compliment subtly defines a boundary: this is what earns you belonging and attention. It’s not the exploration that traps the child; it’s the affirmation attached to it.

The child’s nervous system records these cues. Neurobiological studies in 2020–2024 confirm that social reward activates the same dopaminergic circuits as material reinforcement. A child’s developing sense of self literally wires around these exchanges. By age four, most children can predict which behaviours will elicit adult approval; by age seven, they self-police and mask to maintain it.

In PCT terms, the contract has been signed in the psyche, and the body conforms to it.

When Contracts Collide: The Rise of Incongruence

Now, enter the modern social landscape. Over the last decade, gender has been reframed as an inner, innate identity rather than a set of external expectations or world views. The intent was liberation. But paradoxically, it cemented the very structure it sought to dismantle.

Because if gender is a self-declared identity, then authenticity becomes another performance—another contract to uphold, this time with the self and with a newly ideological society that rewards affirmation. Children are told they can “be anything,” but they are also told what that means: pronouns, symbols, communities, flags.

They’re offered belonging in exchange for covert compliance with a new script.

The gender contract has simply changed employers.

Psychologically, the process mirrors a classic PCT breach cycle:

Expectation: “If I express myself freely/in this way, I’ll be accepted.”

Breach: The “Authentic expression”/internalized expectation still draws confusion, correction, or conditional support.

Violation: Emotional dissonance—“Something’s wrong with me.”

Renegotiation: Adopt new labels, identities or thought-scaffolds to restore reciprocity.

Reinforcement: Belonging returns contingent on performance to the new norms.

Clinically, this looks like dysphoria. But the distress doesn’t necessarily stem from biology; it stems from contractual dissonance—the collision of competing obligations: internal authenticity versus external belonging.

This is where the medical and psychological industry has made its mark and ensured financial long-term viability by overshadowing and reinforcing its paradigm as superior to all others, while self-reinforcing and avoiding accountability.

The Unconscious Machinery of “Care”

To understand how this dynamic metastasizes, we have to look beneath the surface of kindness itself.

Modern parenting and pedagogy often equate “support” with “affirmation.” To protect children from shame, adults mirror their words and identities without interrogation. Yet PCT teaches that every affirmation carries implied reciprocity.

When a parent or teacher affirms a child’s self-declaration—“Yes, that’s who you are”—it feels compassionate, but it also codifies a contractual clause: the adult now owes consistent validation, and the child owes consistent identity performance to maintain that validation.

This is how “care” becomes coercive—how belonging, once unconditional, becomes conditional again. The adult doesn’t see it as manipulation; the child doesn’t register it as pressure. But over time, it functions like any labour contract: performance for approval, and identity for inclusion.

And when the contract frays—when curiosity shifts, or the adult hesitates—the breach is felt as betrayal, a visceral feeling, and ‘dysphoria’, in this sense, isn’t a fixed state; it’s an emotional aftermath of failed reciprocity that continues under the incorrect informational lens of awareness, which then invites itself to experimentation to self-correct.

The Biology of Breach

Modern neuroscience supports this link between social breach and physiological distress. Research on social pain overlap theory (Eisenberger, 2012–2020) shows that rejection, exclusion, and betrayal activate the same brain regions as physical injury—the anterior cingulate cortex and anterior insula. Chronic experiences of unmet expectations—whether in workplaces, families or inter-relationally—elevate cortisol, blunt dopamine sensitivity, and produce symptoms indistinguishable from anxiety or depression.

In adults, we call it burnout.

In children, we often call it dysphoria.

What looks like an identity crisis is often the somatic expression of unmet relational contracts—the body signalling that the social world has broken its promise of safety. When that distress is misdiagnosed as an internal mismatch rather than an environmental failure, we pathologize the individual, medicalize the solution, and self-soothe our consciousness with “we are doing the right thing” so that we can sleep at night. Circular self-reinforcement.

The Profit Motive and the Pathologizing of Dissonance

It’s no accident that the medical model absorbed gender distress so readily. PCT research consistently finds that institutions prefer to individualize breach rather than acknowledge systemic failure—it’s cheaper, cleaner, profitable, and less of a PR and change-management nightmare.

In corporate life, the worker who burns out is “unfit,” not the system that overburdens him. In gender medicine, the distressed child is “born in the wrong body,” not raised in the wrong expectations.

The pharmaceutical model then steps in as the contract’s new enforcer, offering relief through compliance. Puberty blockers, hormones, surgeries—all framed as fulfilling the body’s end of the bargain. But the data, as ongoing reviews like Cass (2024) show, remain weak to nonexistent for long-term benefit, and the psychological outcomes mirror those of unaddressed social alienation.

The contract holds, the child changes, and the system profits—a pattern many adults recognize much later in life as they leave roles, environments and relationships that once purchased belonging at the price of self.

The Deep Misinterpretation: Dysphoria as Contract Violation

If we reframe dysphoria through the lens of PCT, a different picture emerges:

It’s not definitive evidence of an inborn incongruence.

It’s a signal that the implicit agreements between a child and their environment(s) are unsustainable.

It’s an accounting error in a system of unspoken promises.

It’s a marker of mismatch between a child and context—calling not for the child’s conformity to an idea, but for contextual change that accommodates difference.

The body doesn’t lie—it registers breach as pain. But we have mistaken that pain for proof of identity rather than the residue of expectation.

In that sense, dysphoria is a logical outcome of modern covert social conditioning. A body trying to renegotiate its contract with a world that keeps rewriting the terms. A body that has many contracts, depending on the number of environments it finds itself in.

Toward a Broader Lens

This isn’t a manifesto against gender-diverse expression. It’s an argument against the pathologizing of normal human variance and the blindness to how our praise, care, and “progressive” policies perpetuate invisible obligations and psychological contracts that feed off of our neurobiological need to belong and feel safe.

Psychological contract theory gives us the framework to see the hidden architecture beneath ideology—a map of the subtle emotional economics that govern identity formation. It tells us that most suffering doesn’t emerge from essence but from exchange.

We can’t understand the explosion of gender confusion without tracing the unspoken contracts that preceded it:

the moral contracts of approval,

the parental contracts of care,

the cultural contracts of progress.

These aren’t malicious. They’re unconscious. But they’re binding.

The Unwritten Future

Before gender became identity, it was labour—divided, assigned, and enforced. Before “dysphoria” became a diagnosis, it was discomfort with the deal.

Psychological contract theory doesn’t solve the crisis; it reveals an overlooked and inconvenient part of the scaffolding. It shows us that our children’s confusion may not be the problem—but rather, the only sane response to a society that keeps changing the rules of belonging and calling it compassion.

If we are to move forward, we must first learn to see these invisible contracts for what they are: not proof of who we are, but of how we’ve been taught to earn love.

The real question is this: when will we stop allowing society and its institutions to dictate conformity—even through the most extreme and medicalized means—of both gender-dysphoric children and medicated adults alike? How long will we pretend that the problem lies in the individual, when every sign points to an environment that no longer works? Perhaps it’s time to ask not how to fix the person, but how to rebuild the world that keeps breaking them.

Take heart,

Jason

Great article! I would suggest that markers of gender are not entirely social or arbitrary. For example, a beard used to be a fairly reliable indicator of an adult male, even though rare endocrine conditions could create 'bearded ladies'. Today, some women deliberately create endocrine disorders in their own bodies in order to be validated as masculine.

Your example of a boy holding a doll was really interesting. These days, men are encouraged to hold their young children, and a young boy might see their father or another adult male doing exactly that. So why is a boy holding a doll still feminine-coded? Is it because some adults dislike masculinity and would rather that boy was raised to think of himself as feminine?

This is deep! Thank you for this.